auf Deutsch

en français

magyarul

- What is FactGrid?

- Why should I use FactGrid for my own research?

- Why not use Wikidata right away?

- FactGrid comes free of charge – how does that work?

- What do I do with unorthodox research interests?

- Which tools does the software provide?

- What do I do if I want to give my very own data representations on my own platform?

- FactGrid basically licenses data to CC0 – does that not mean that I give up all rights to my research?

- What happens if I want to continue working with my data on another platform?

- What happens when FactGrid users argue about a “correct” date?

- Why should I risk transparency in my project right from the start?

- How do I get my project accepted on FactGrid?

What is FactGrid?

FactGrid is a Wikibase installation — that is is both, a regular wiki and a database which you can use to make statements about objects of your interest — statements which you can then handle in practically any language in big data sets.

The platform is run by the Gotha Research Centre and hosted by the University of Erfurt. It addresses projects with a specific interest in historical data and is part of the German National Research Data Infrastructure NFDI4Memory.

In joint ventures with Wikimedia Germany and the German National Library’s GND we are trying to bring this platform into the upcoming consort of federated Wikibase instances as a resource for research data.

Why should I use FactGrid for my own research?

The biggest argument for a FactGrid account is the unbeatably flexible software, Wikibase, which we have managed to implement in a pilot project with the help of Wikimedia Germany – outside its primary location, Wikidata:

- You are looking for a software that speaks practically any language — a platform on which you can enter data in your language and allow others to read your data in their languages? Wikibase is this software.

- You are looking for software in which you can transparently coordinate a whole team? In Wikibase this is as easy as in the Wikipedia software MediaWiki .

- You are looking for a database software that can do everything Digital Humanities databases normally want to do: network analysis, map representations, complex linked searches, timeline representations (in various formats) – a software that almost acts like human language yet provides full database services? Wikibase is this software.

- You have data from previous projects which you want to build on? Wikibase has large-scale automatic input options.

- You want to make sure that that other projects will actually use your data? Use a platform that allows the download and further work with your data offline in Excel or online in ever new projects.

- You want to ask entirely new questions in your research? In Wikibase you can link any sort of objects with any kind of statements of your interest.

- You are worried what will happen to your data and presentations once your funding is over? Work on a platform where you do not stay alone and where, thanks to the CC0 license you are using, you encourage colleagues to continue right were you stopped!

If you are looking for a long term perspective this is what we are trying to offer in our present joint venture with the German National Library. We will base our platform on GND data in order to serve as a broad public tool and with the aim to become a player in the emerging landscape of “Federated Wikibase installations”.

Why not use Wikidata right away?

That is a legitimate question to ask. There will be projects (projects that are mainly using data) for which Wikidata will be the better platform. The FH Potsdam’s “Archivführer zur deutschen Kolonialzeit” has demonstrated the beauty of working directly on Wikidata; we talked about this with Uwe Jung, who demonstrated the technical solutions they have chosen in Potsdam.

On the other hand, there remain basically two things which you will not be able to do on Wikidata or on a platform like the GND: Wikimedia projects (and the GND) have strict “No original Research” policies and observe fundamental decisions to operate on “criteria of notability“, which will not allow the arbitrary opening of database objects and the innovative object relationships researchers would like to test.

Wikidata and the GND focus on information that has already been published and on non-research workers who feed the respective databases from published research. You will not be allowed to state a “working hypotheses” of “your research” on these platforms. You will not be able to create entities with the aim to run “nothing but a statistical analysis” on them at a far later stage of your work.

In FactGrid we encourage the use of the platform as a heuristic research tool.

- Create database objects on the platform, no matter what their relevance in an encyclopedia or in library catalog could be.

- Risk provisional chronologies as working hypotheses along with your personal assumptions.

- Use FactGrid in order to make unconventional statements that are presently interesting only in your research project – the software gives you this freedom.

- Create specific database objects that state your research in all the data sets which you have substantially modified and become able to submit your research with the particular item as the envelope to your funding institution.

- Risk any new thesis on the platform and state your respective view with a database object number as a “micro-publication” in order to claim your ingenuity on the data base.

FactGrid is free – how does it work?

The software is freely available and under development in the larger community of Wikimedia projects and among the institutions which are going to use Wikibase over the next years.

The FactGrid platform is presented by the Gotha Research Centre on a virtual server of the University of Erfurt. The German URL costs €36 domain fees per year, financed by the Gotha Research Centre.

All the Wikidata-tools are available to our users. These include all the standard applications of regular Digital Humanities projects.

With both software and tools being open source you can use any favorite software company you are working with, to generate the specific application which you feel you need.

If you feed your tools into the open compound this will be your best way to make sure that future projects will continue their development.

If you aim at technical solutions which you want to sell with financial profit that again will not be restricted by the software license. You can freely commercialize whatever you create on the basis of the open software.

What do I do with unorthodox research interests?

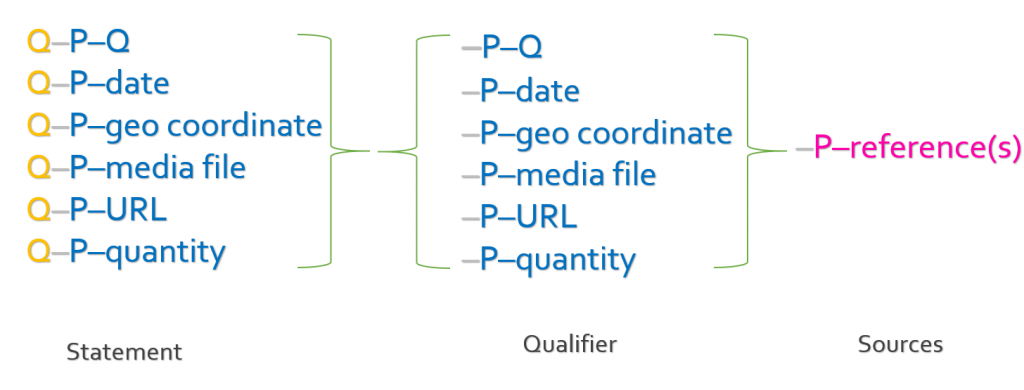

Wikibase is groundbreaking in its data modelling. Essentially you are only creating relations between Q-numbers (or relations between Q-numbers and dates, Q-numbers and space coordinates, Q-numbers and media files, Q-numbers and URLs).

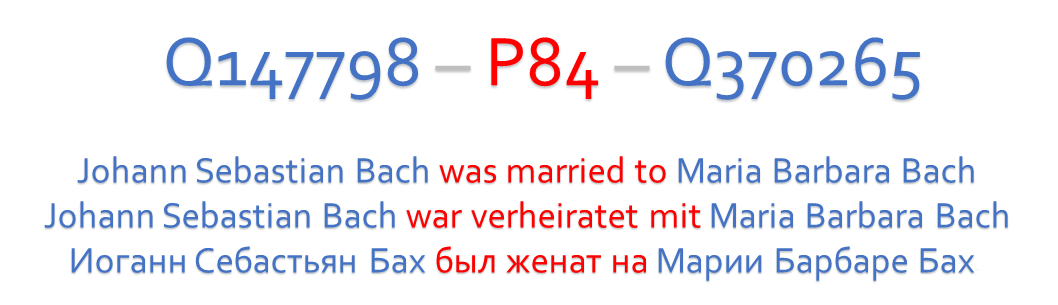

The software does not know what kind of relationships you are stating – these again are just P-numbers: Q1 – P1 – Q2 is a “triple” and can mean “Johann Sebastian Bach (Q1) is the father of (P1) Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Q2)”; it can mean just as well “This letter which I found in the archive with the shelf mark XYZ (Q1) has allegedly been sent from (P1) Munich (Q2)”

Q-numbers can be assigned to anything imaginable – people, documents, events, ideas… You decide what kinds of P-numbers you need in order to make statements of your interest. You do not define objects in a system of fixed categories; your statements are adding colour and solidity to whatever object you create as you go along. Do not worry if you do not have the data model on day one. Make statements when you suddenly want to make them and see how they gain the critical mass that can eventually be evaluated.

All statements can be “qualified” – “Johann Sebastian Bach (Q1) was married to (P2) Maria Barbara Bach (Q2) beginning on (P2) October 7, 1707 (date) ending (P3) about July 5 1720 (date).” All of these statements can in turn be equipped with references : “this is clear from (P4) the church book of… (Q3)”,”this is stated in (P5) the well known Bach biography XYZ (Q4)”.

The system allows competing claims at any time. They are simply introduced with their different sources and can be balanced against each other.

You can create practically any normal language statement with triples of this depth of specificity; but above all, this opens the door to the world of statements in all the various languages you might want to speak: The system operates with Q- and P-numbers; the rest is labels in languages which you want to offer to your users. The software will in addition translate dates and quantities into other formats; this is basically the secret that makes it possible for Wikibase platforms to be edited by people in their own languages and to be read by the world in practically any other language.

Which tools does the software provide?

Database entries can be made one by one: Open the object-id in question, go to the bottom of the input page and click the “add statement” link. You will now be asked for the statement you want to make. You do not need to know the P-number. State the property in the language you are using and click at the auto complete you are eventually being offered. The platform will now use the P-number of that statement for you. Complete in the next box that opens your statement. You will again get suggestions to use as you are typing.

Database entries can also be created and substantiated in automated inputs from Excel or CSV lists. (This is the input mask and this is the short guide to it.)

Database queries have to be formulated as “SPARQL” queries, a search language that is (unfortunately) not that easy to use, but that is eventually as complex as the searches you might want to perform.

SPARQL users do not necessarily know how to write SPARQL source code. You usually use sample queries that tell you where you have to change the input in order to run your particular search.

If you know exactly which type of search queries your users should run you can create your own input masks just as you know them from conventional online library interfaces, which will then speak SPARQL with the database.

The software package includes illustrations on maps, timelines, networks, genealogical relationships, graphs, and so on. You do not need to download particular applications. You will ask SPARQL to produce the representation you are trying to get. The Scholia project on Wikidata has a beautiful first presentation of some of the visualisations.

What do I do if I want to give my very own data representations on my own platform?

That should not be a technical problem. Uwe Jung demonstrated how the FH Potsdam interface uses Wikidata as its data repository, without letting users see the database they are accessing.

There is nothing wrong with using FactGrid as an external repository and building up your own research project on the server of your home university, where you can offer targeted database accesses under a typical search template of your choice.

FactGrid basically licenses data to CC0 – does that not mean that I give up all rights to my research?

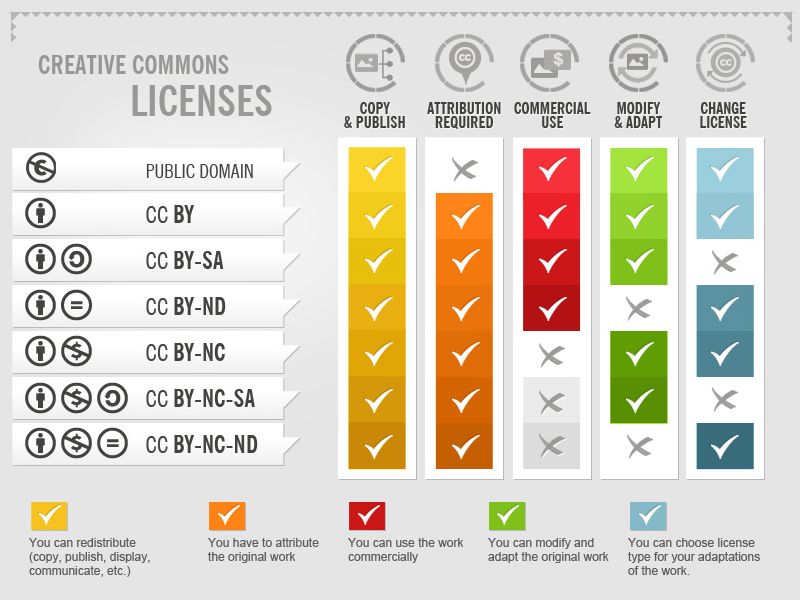

Opting for the Creative Commons 0 license means essentially that you continue to be free to do whatever you want with your data – you, and not your publisher or the platform that received your data under a scheme, continue to control. But above all, the CC0 license means that your data becomes freely usable and that you can thus reduce the danger of obsolete research in the longer run – others will continue to root out the ugly mistakes you could not hope to correct.

Some basic considerations: CC BY 4.0 is at first glance the license that scientists will prefer: It allows the free further use as long as it receives the accurate citation. In practice, this will work for texts (such as this blog post); here it is clear how one would like to see the text cited: with a reference to one’s own name, with the title of the publication, the place of publication and the date. But do you want your data quoted let us say in a visualisation? A letter sent from Paris to Berlin in June 1753 will be a line on a map and how should this line be properly annotated? How do you want to be quoted if you only improved a data set? “Share alike” licenses are even more problematic: “These data are freely available if the subsequent users keep it just as freely available.” That sounds like the ultimate plea for free use. But how can a sub-user ensure that his sub-users, in turn, will respect your license agreement (especially if this sub-user is offering his data on CC0)? Sub-users are well advised not to use data from CC-BY or CC Share-Alike platforms.

Our joint ventures with Wikidata and the German National Library left us only only one option: to make our data as freely available as our partners: CC0, that is without ensuring that subsequent users will still specify exactly who collected the data, and what third-party users are allowed to do with that data.

In practice, the maximum open license does not mean that FactGrid data is data without authorship, quite the contrary. We suggest that research is cited and assume that Wikidata and the GND are only too happy to state research from our platform. All changes are linked to respective the author names. If research projects have worked more substantially on a data set, they will have stated this in a separate note on the data set that can now be adopted with the data transfer.

Databases like Wikidata or DNB’s GND are in fact interested to quote research – it boosts their data solidity, and FactGrid is here in the unique position to give both institutions a platform on which people can do what they cannot do on the respective larger platforms.

What happens if I want to continue working with my data on another platform?

Since you entered your data without a copyright restriction, you are free work with them on any other project of your interest. We actually like to be “just an incubator” for research data.

What happens when FactGrid users argue about a “correct” date?

The software makes it possible to handle contradictory data. This is particularly interesting in the field of historical research, where we often have conflicting documentary evidence without being able to determine the correct statement after so much time. The software makes it possible to reproduce such a contradictory situation. Numerous statements can be given side by side with their various respective sources. You can then still balance the statements against each other – either by turning one of them into the statement to privilege in future searches and/or by adding qualifying statements with your personal evaluations.

If two researchers come to different results, think of it as the situation you should actually be interested in. It is far worse that you have made mistakes on a platform where they will never be corrected and where they eventually discredit all your work as obsolete beyond repair.

Why should I risk transparency in my project right from the start?

This is likely to be the toughest issue that currently prevents projects from using the resource which we have opened. The alternative is the resource, which is accessible to the team only under passwords until the publication deadline is reached almost at the end of the project. No competing project can snatch away findings, so the theory. No one sees where you have initially made a mistake. Nobody records what assistants are typing in and where the project leader is involved – such are the presumed advantages of non-transparent working on a platform that will only go online at the end of your funding.

Transparent research offers its own securities: If you find a groundbreaking document and establish a decisive connection, then this is your chance to fix the statement to your name and project. If someone makes the same discovery tomorrow in the archive you have just visited, tough luck. You will have recorded your observation with a link in the version history which your rivals will not be able to deny.

At the same time, the collective platform expresses the invitation to cooperate. Make it clear to other teams what you are working on and allow them to contact you on the platform!

The risks of the allegedly secure website, which is only going online at the end of the project’s funding, are serious: The time for an exchange with users is over. The internet presence goes online in the heated final weeks while the project is totally unable to react with more conceptual changes. If you have done research solely for a book publication, it will remain unclear what you and your team should do with the data, you have still collected in Word files, and Excel spreadsheets. Nobody will be able to feed all these data into any resource – the harmonisation at this late stage will be an insurmountable obstacle. You can only hope that readers of your book will scan all your footnotes for corrections that should reach our library catalogs and the various Wikipedia projects. The risk is here the book that has no influence on the collective data base and of DH projects that become obsolete right after their publication.

The future should lie in a new attitude toward the public data base. Researchers should be able to correct and to further widen this base wherever they access it. The incentive and the security they will need here is the research environment in which they can mark their work and make it citable. For this Wikibase is better equipped than any other software.

How do I get my project accepted on FactGrid?

The FactGrid platform has no invisible deeper layer. Anyone can query the database and the queries will give the same information whether you are logged in or not. Your personal user account just has the advantage that you can now switch to your favorite language when looking at data, and that you see the edit link on each statement.

If you want to feed your own data into the platform and if you want to run a project on the the platform, you will need an account. These are given under real names by the administrators. The software provides an “account request” link. You can also contact us via email. Project leaders can receive administrative accounts which they use to assign to team members and users of their interest.

Once logged in, you can enter data in bulk or make specific corrections wherever you feel like. Any input will be connected to your user account. Others can undo your edits but not without leaving a documented mark of that intrusion in the version history – visible to all the world.

If you want to work on a more complex project —

- that can be personal family research,

- it can be a single visualization you need in a seminar paper,

- it may just as well be the input of thousands of records in a 5-year research project

— speak with those on board and those organising the platform. We will not (necessarily) be interested to sign a public memorandum of understanding with you but it might be cool to advertise your project on the blog and to make it known on the entire platform. Your work becomes exciting, where you modify the work others have already done and where you encourages players from other projects to adopt good models which you are introducing. You do not need to discuss data models with all the others but using models with all the others is also a way to spread your work and to make it appear in queries composed by others, and visualizations you did not think of.

The software is designed to manage both: unique statements which only you are interested in and statements that will spread far beyond your own initial research interest as you are now feeding the unforeseen queries which others will run on their and your data.

Dear Colleagues,

We are writing a proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities to move the PhiloBiblon databases at Berkeley (https://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/) from its legacy software (Windows relational dbms + eXtensible Text Framework (XTF) to another platform. WikiBase has been proposed and FactGrid is listed as a model. Your list of FAQs suggests that in fact PhiloBiblon could be incorporated into FactGrid. It would be enormously helpful if I could speak with someone (in English, despite my name). Many thanks,

Charles Faulhaber

Let us talk about it in in a video call, I sent you an email. All this is a wonderful project.

Best wishes, Olaf