Thanks to the initiative of Andra Waagmeester and Daniel Mietchen (who are part of the community that is behind Wikidata incorporating such staggering inputs as the complete human genome) we ventured a first workshop of projects that have begun to use the Wikibase software outside the original Wikimedia/Wikidata environment. The event at Antwerp’s fifteenth-century hospice, now the Elzenveld hotel and conference centre, was generously funded by the European Research Council. The participants came from fields which only this software would bring together: the natural sciences, the humanities, the social and political sphere and Wikimedia. Wikidata, the Wikimedia project in the centre, is about to become the broadest compound in the world of collaboratively produced knowledge. Starting with interconnecting the 290 Wikipedias all around the globe it became able to switch between all their respective languages. Knowing all the equivalents of articles as well as all the unique items which individual communities created on their Wikipedias Wikidata is closer than any comparable compound to theoretically knowing what a father, a cat, a religion or a novel structurally is. The multilingual competence is matched only by the database’s openness to all sorts of items: Wikidata is dealing with bacteria, the Mona Lisa, Chinese politicians, obscure philosophical concepts, mathematical equations, individual genes, geo-coordinates, and all sorts of properties and qualities these items can gain. The software is open to the flexible creation of ever new properties interconnecting the bricks. You can read Wikidata on the Reasonator and you can explore Wikidata with machines. It is open to logic, accessible in ever new SPARQL queries – the search language worth learning.

Why federating specialised Wikibase platforms will be a win/win situation for Wikidata and the emerging sister projects

Wikidata has overtaken the individual Wikipedias as a project attracting masses of specialised data. Anyone can contribute. The input can be done by machines – so why not the complete human genome? It is at the same moment no longer clear whether Wikidata is the ideal place to host such infusions. Should Wikidata risk the input of all the astronomical objects that have been referenced – of billions of stars creating usually little more than a number and the information of the original observation? This is not only a question of the software’s technical abilities; it is far more a question of the communities needed in order to keep the data easily accessible and up to date.

The alternative is the environment of interacting, more or less specialised platforms that use the same software and that exchange data wherever that is of interest. The win/win situation will have more than one dimension:

- Wikidata is saved from a flood of information which no Wikidata community can offer to keep attractive.

- The individual platforms can establish their own workflows and professionalised user rights managements.

- Wikidata would function more as the bridge between various databases, referring to knowledge elsewhere – a uniquely attractive position.

- The individual platforms would win visibility and sustainability in the compound – with Wikidata as the central supplier and distributor of information used all around the globe.

A wikibase compound to interconnect the emerging community

The workshop was immensely practical. The central product was not a mission statement of a future collaboration with tight pledges and attempts to institutionalise the emerging field. We were far more eager to discuss software problems, development plans, and to share practical experiences.

The two Wikimedia software developers, Adam Shorland and Raz Shuty, entered a sportive hunt for the stream of “tickets” that emerged in the various debates which Wikimedia’s Sandra Müllrick helped to organise in ever new groups.

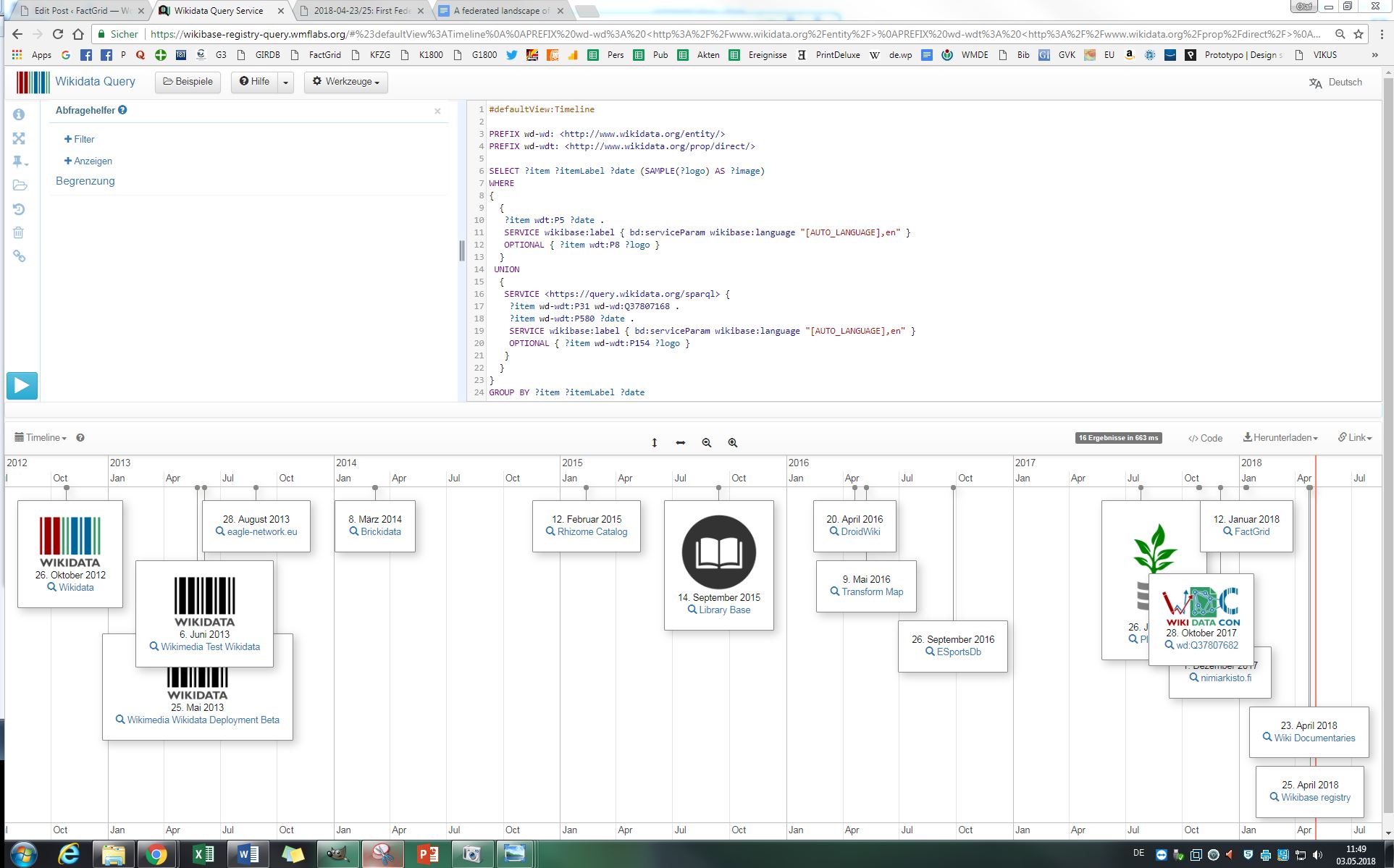

Instead of the mission statement we created a further Wikibase instance with the primary aim to map all the projects that have begun to use the software. A retrospective timeline came gratis with the register:

Desirables

It was apparent that we had all been facing technical problems. Some of the projects found their own solutions, others tried to engage Wikimedia as the software’s mother. It was clear that we will all learn from each other and we should aim to make the practical know how we are individually gathering accessible to future projects.

Wikimedia’s Wikibase software is more versatile than any other comparable database software on the market: it is prepared to deal with a constant flux of concepts and specifically designed to adapt to open growth but it is not yet addressing “normal” users, users who are not primarily interested in the technical solutions they are getting here. The SPARQL query is a brilliant key to mine information, yet it is not a language a coincidental Google visitor or a professor of history organising his team will be immediately able and ready to use. Projects will face a need to develop conventional interfaces that will then secretly speak SPARQL in its further dealings with the database.

We will face similar needs to develop web forms which regular users can handle to contribute their knowledge.

Wikimedia – this was the encouraging signal Sandra Müllerick, Adam Shorland, and Raz Shuty were giving as a formidable team of problem solvers – is interested in the increased use of its new product. New projects are encouraged to test the software and if that is of use to them: to become platforms in a far wider compound of projects that can do what Wikidata should not aim to do.

Projects creating the new compound should at the same moment embrace the chance to meet, to learn from each other, and to exchange data. Any data exchange will create new perspectives on their respective fields, it will inspire new tools, it will promote their work in the growing environment of data driven research. The Wikibase software will become common over the next decade.

Our conference was a first meeting and an attempt to look across the borders of our respective fields. We decided to stabilise this exchange; a follow up meeting with probably more participants in New York is in the pipeline.

Details & Links

The Participants

- Susanna Ånäs (Finnish Name project; Open Knowledge Finland)

- Diego Chialva (Policy Analyst, European Research Council Executive Agency)

- Davy Cielen (Data Scientist, Contractor at the European Research Council Executive Agency)

- Rajaram Kaliyaperumal (LUMC, Leiden The netherlands)

- Lozana Mehandzhiyska London (South Bank University & Rhizome)

- Daniel Mietchen (Data Science Institute, University of Virginia)

- Lyndsey Moulds (Rhizome)

- Alexis-Michel Mugabushaka (Policy Analyst, European Research Council Executive Agency)

- Sandra Müllrick (Wikimedia Germany)

- Nuno Nunes (Maastricht University, Maastricht)

- Adam Shorland (Wikimedia Germany)

- Raz Shuty (Wikimedia Germany)

- Olaf Simons (Gotha Research Centre of the University of Erfurt)

- Greg Stupp (Scripps Research Institute)

- Elena Toma (Policy Analyst, European Research Council Executive Agency)

- Andra Waagmeester (micelio)

Presentations

- Alexis-Michel Mugabushaka: Potential of Open/Linked Data for Monitoring and Evaluation – The case of The European Research Council (ERC)

- Andra Waagmeester, Dragan Espenschied & Daniel Mietchen: Wikibase Workshop Antwerp

- Adam Shorland, Raz Shuty & Sandra Müllrick: A federated landscape of Wikibase

- Gregory Stupp, Andra Waagmeester & Andrew Su Lab (The Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA, USA): The Gene Wiki Project

- The Wikibase usecase

- Lyndsey Moulds (Rhizome) & Lozana Rossenova (London South Bank University & Rhizome): The Wikibase usecase for Rhizome’s ArtBase

- Susanna Ånäs (Open Knowledge Finland): This was yesterday

- Olaf Simons (Gotha Research Centre of the University of Erfurt): The FactGrid Project

- Rajaram Kaliyaperumal: Past and Expectations

- Adam Shorland: Past Present Future?

- Nuno Nunes (BiGCaT, Maastricht University): Wikibase Workshop

- Daniel Mietchen: Enabling Open Science: Wikidata for Research (Wiki4R), WikiCite, Scholia

Links

- The Conference’s organisational Google Doc

- The immediate digest at Wikidata:WikiProject Wikidata for research/Meetups/2018-04-23-25-Antwerpen

- The Wikibase Registry of projects using the Wikibase Software

- Adam’s post on how the registry was set up

- Follow-up Workshop in Berlin, 15 June 2018: https://blog.wikimedia.de/2018/07/13/wikibase-workshop-in-berlin/

One Reply to “2018-04-23/25, Antwerp — the first Federated-Wikibase-Workshop”